The English language is Anglo-Frisian, not Anglo-Saxon

The European language that is most closely related to English is almost certainly Frisian. English is part of a small group of Germanic languages known as Anglo-Frisian. The earliest version of English became Anglo Saxon as the English merged with the incoming Saxons and Angles.

The present day distribution of Anglo-Frisian languages in North West Europe is shown in the map below.

The blue area is where Frisian is still spoken today. The yellow areas are where English is widely spoken as a first language. Everyday words in West Frisian and English are strikingly similar.

This answers an obvious question: why is England pronounced with an “i” when engage, engorge, enwrap, entwine etc. use an “e”, as in “egg”, sound? It is intriguing that Yngvi (probably pronounced ingwi, and Ing in old English) was the ancestral God of the Ingaevones. The Ingaevones were Angles, Frisii, Chauci, Saxons, and Jutes. The West Frisian word for the English is Ingelsk (probably: beloved of Ing) .

It has always seemed strange to students of the English that they were named after the Angles despite the Saxons becoming the most powerful rulers. The Jutes and Saxons were often at war with the Angles and would have been horrified to use Angleland as the name of the country. However, as will be seen below, even the Germanic Belgae and Atrebates could have accepted Ingland as a common name for the Germanic country. The written name would have changed with the rise of Christianity to something less pagan such as England.

We are taught in school that the Anglo-Saxons invaded England in the 5th century and gave rise to the English. The Saxons and Angles did indeed invade in this period but there must be grave doubt that the English language and People came solely from this invasion.

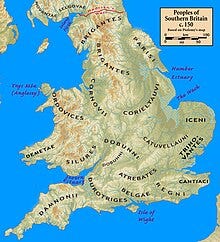

There were many incursions into SE and E England from the near continent during the first millenium BC. In particular the Belgae established a cross-channel presence in southern Britain as well as in what is now North East France and Belgium. Around the time of the Roman invasion their descendants formed tribes in the areas on the map below labelled Belgae, Atrebates, Regni, Cantiaci, Catuvellauni:

Julius Caesar notes the close relationship of the Cantiacci to the Belgae in his “Conquest of Gaul”. He also notes that the Belgae were mixed German-Gallic. The language spoken by this group is not known for certain but, given that English is Anglo-Frisian and hence pre-Anglo-Saxon, we can guess that they spoke a version of Anglo-Frisian. Caesar recorded that the Belgae had their own language:

“All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae inhabit, the Aquitani another, those who in their own language are called Celts, in ours Gauls, the third. All these differ from each other in language, customs and laws.”

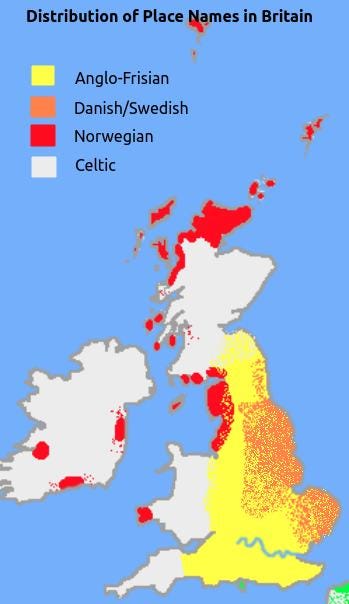

The place names (toponomy) in Britain reflect an early Germanic influence in England, the areas of strong colour on the map below crudely shows the preponderance of each source:

It is interesting that whenever the language of pre-Anglo-Saxon England is discussed many academics bridle at the thought of it being Anglo-Frisian, not because this might not be true but because it might encourage English nationalism. Of course, just the plantation of thousands of Frisians in the SE of England by the Romans (as Federati) should be enough to raise a huge question mark over the nature of the pre-Anglo-Saxon English population.

The genetic maps of Britain also show a clear division between SE /E England and the rest. Studies of the genetics of ancient skeletons that date to the fifth to eighth centuries AD also show considerable input from Frisians, Angles, Saxons and Jutes (red colour in map below):

See Ancient DNA reveals details about early medieval migration into England (Gretzinger et al 2022). (EMA CNE: Early Middle Ages skeletons with Continental North European related genetics, Map re-coloured for clarity).

The conclusions of this study do not take account of the linguistics nor the history nor the various burial customs (cremation destroys skeletons) but the study is interesting. There were probably already Germanic tribes ruling SE England who spoke Anglo-Frisian before the Roman invasion and these may have been closely related to the Frisians, Angles, Saxons and Jutes. This means that genetic data showing Germanic input should be interpreted with care. In particular Germanic ancestry does not mean that an individual skeleton was descended from Anglo-Saxon ancestors but could also have been derived from earlier Belgae or Frisian settlers.

A more recent study, “Local population structure in Cambridgeshire during the Roman occupation” (Scheib et al 2023), shows that remains of people from the Roman period have Identity By Descent (IBD) sharing of 10% for Germanic ancestors whereas remains from the Anglo-Saxon period rise to IBD sharing of 15%. This seems to confirm that two thirds of German genetic material in English people was acquired in Roman or pre-Roman times.

The most likely story of the English is that during the first millennium BC there was a considerable interchange of people between the SE of England and the European continent. This was due to both invasion and migration. The result of this movement is that the the governing class and many of the people of the SE of England were related to the Frisians and spoke an Anglo-Frisian language although the population may have had a high French/Celtic genetic component. English people with English ancestors still have about a third French ancestry and a third Celtic. In the 3rd century AD the Romans also settled some of the conquered continental Frisian population in SE England as laeti (colonists).

The Romans left Britain in 409/410 AD and within 40 years the Celtic and Anglo-Frisian parts of Britain started a civil war . This war may have been partly due to religious differences (Pelagianism) and partly language and cultural differences. Vortigern was the ruler of SE England and he invited thousands of mercenaries from North West Germany (Angles, Saxons and Jutes) to fight for his side. Vortigern did not pay the mercenaries so they mounted a coup.

The civil war seems to have continued after the coup and reached stalemate after the Celts won the battle of Mons Badonicus in about 500AD.

It is interesting that the pre-Roman tribes of Southern Britain had territories that correspond to English counties and also correspond to the early Western Saxon, Southern Saxon and Jutish kingdoms.

The Jutes even called their kingdom Kent after the Cantiaci. Perhaps the pre-existing Germanic tribes in these areas continued with an injection of mercenaries. The areas were known as Saxon and Jutish as the mercenaries became rulers and prospered.

The Inglish were fairly genetically isolated for almost a hundred generations until, in the late twentieth century, their governments implemented a policy of massive population growth by importing people from all over the world. In the past 15 years alone the population has grown by 10%. Within 20-30 years the Inglish will be a minority in England. This policy was repeatedly approved in elections.

Note 1: Sources such as Bede and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle are equivocal about the English. This excerpt from Bede's Ecclesiastical History of England, Chapter 22, for circa 449-500AD describes how the cities were destroyed before the civil wars of c450. Bede also distinguishes Saxons and English, suggesting that the civil war was with an English population that was already in Britain:

“In the meantime, in Britain, there was some respite from foreign, but not from civil war. The cities destroyed by the enemy and abandoned remained in ruins; and the natives, who had escaped the enemy, now fought against each other. Nevertheless, the kings, priests, private men, and the nobility, still remembering the late calamities and slaughters, in some measure kept within bounds; but when these died, and another generation succeeded, which knew nothing of those times, and was only acquainted with the existing peaceable state of things, all the bonds of truth and justice were so entirely broken, that there was not only no trace of them remaining, but only very few persons seemed to retain any memory of them at all. To other crimes beyond description, which their own historian, Gildas, mournfully relates, they added this—that they never preached the faith to the Saxons, or English, who dwelt amongst them. Nevertheless, the goodness of God did not forsake his people, whom he foreknew, but sent to the aforesaid nation much more worthy heralds of the truth, to bring it to the faith.”

Given that England was occupied by the Belgae for 600 years before the period to which the text above relates, the obvious interpretation is that the English occupied England and the causes of civil war were that there were two languages in Britain and the English had not been fully converted to Christianity or were Pelagians. They made common cause with the Saxons who were closer in culture and language to themselves.

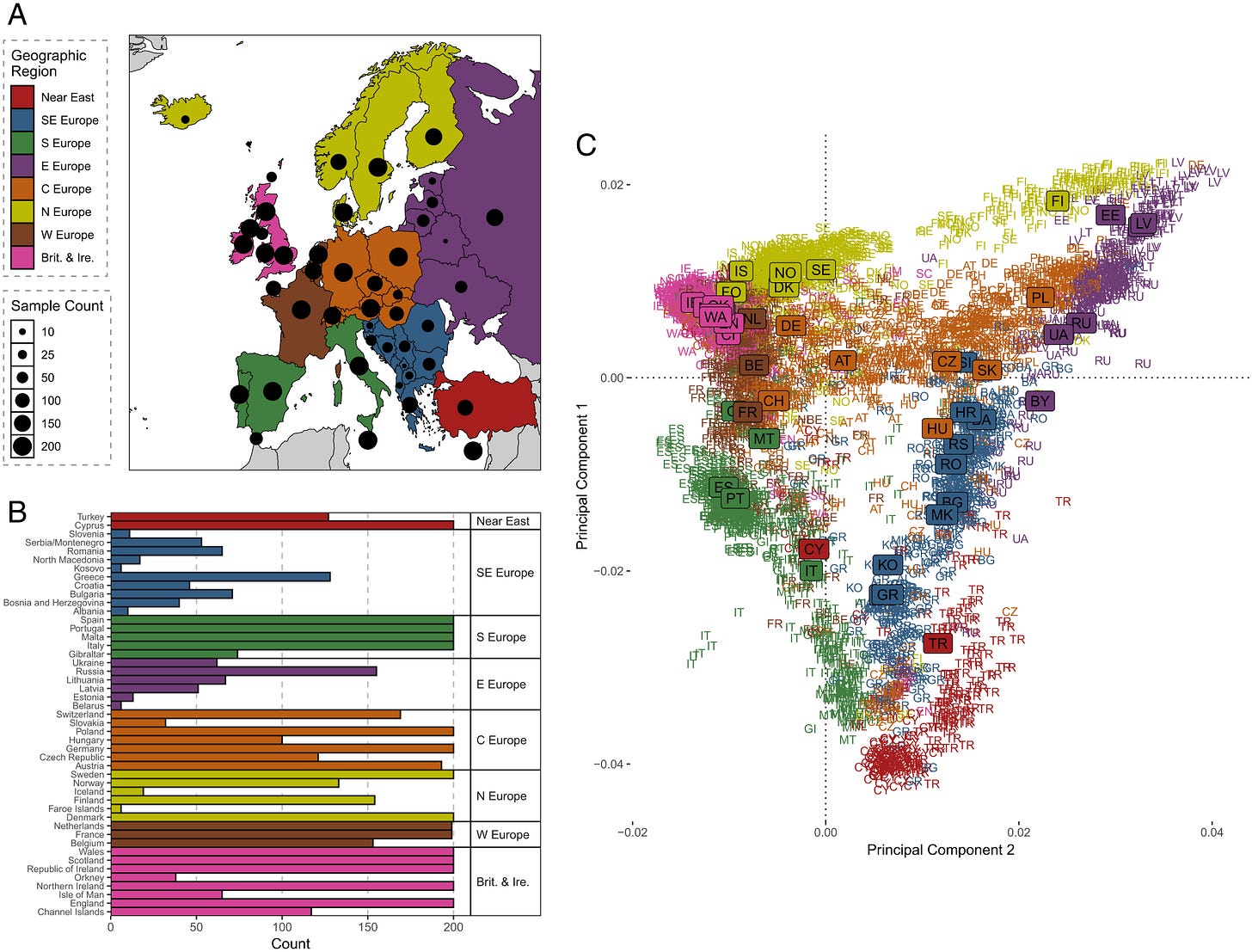

Note 2: The DNA of modern Europeans with local heritage is probably the clearest guide to the origins of any modern group because it is not confounded by burial practices or by assumptions such as comparing a particular area of Europe with British genetics.

The map below shows the clear relationship of the English to people in the Netherlands and Belgium (descendants of Belgae/Frisians). See Revealing the Recent Demographic History of Europe via Haplotype Sharing in the UK Biobank)

The genetics of the British Isles matches the known history: a fairly ancient population in the West that has been isolated for a long time and a related population in England that has experienced repeated migration/invasion from the near Continent. The input from Frisia/Netherlands and Belgium probably came with the invasions of the Belgae in pre-Roman times and some Frisian settlement in the Roman period, this input would also have contained some French ancestry. The input from Germany and added input from Frisia and the Netherlands came with the Frisians, Angles, Saxons and Jutes. The input from Denmark and Norway came with the Vikings.

They were never asked.