The UK has a problem with growth and this is due to poor productivity: the British earn less from each hour worked than people in many other developed countries. The reason for the poor productivity in the UK is often said to be a ‘mystery’.

There is no mystery. Fixing the productivity problem will take time but it can be fixed.

There are two types of productivity problem in a large economy. The first is ‘low tech production’ and the second is imbalanced production. The UK also has hindrances to high productivity such as expensive energy and regulations.

‘Low tech’ production has become a habit in the UK. The problem arises because companies have two ways to make a profit. They can produce goods and services using technology and a few skilled staff or they can produce the same amount of goods and services using large numbers of cheap staff. Cheap labour has a major role in undermining UK productivity (see below). The cheap labour is obtained from abroad.

The UK could move away from a cheap labour economy by leaving the ECHR so that workers can be sent home when their contracts expire, the number of contracts reduced and foreign workers steadily replaced with workers trained in the UK. This would be complemented by cheap loans to businesses for projects that improve productivity.

Imbalanced production occurs when the government favours sectors of the economy that have low productivity or sectors that provide little benefit to the rest of the economy.

Imbalance has three main causes.

The first is a bloated, low productivity, Public Sector. The ratio of the productive private sector to the less productive public sector could be improved by reducing the tax burden and cutting the Civil Service.

The second cause of imbalance is investment in the economy by foreign companies (FDI). These pose as ‘British’ production but actually operate plants that assemble foreign components. The profits are sent overseas. This production does not benefit the whole economy and starves UK industry of business. The export of profits and the use of UK factories for assembly rather than production could be reduced by ensuring manufacturing remains in UK ownership and discriminating against foreign owned UK companies that use over 30% foreign parts.

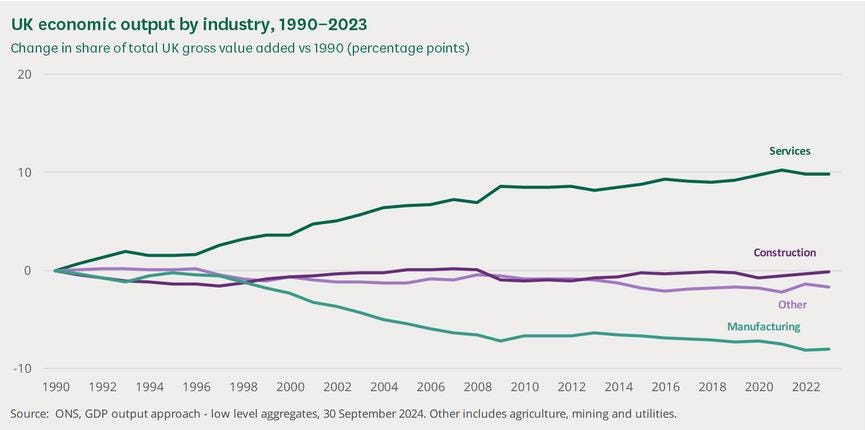

The third cause of imbalance is that Services are viewed as more productive than manufacturing. This was true 50 years ago but modern manufacturing is now highly productive thanks to automation. Only Financial and Insurance services are nowhigh productivity Service industries. The old strike prone factories of the 1970s are a thing of the past. The economy needs a return to manufacturing, high productivity manufacturing.

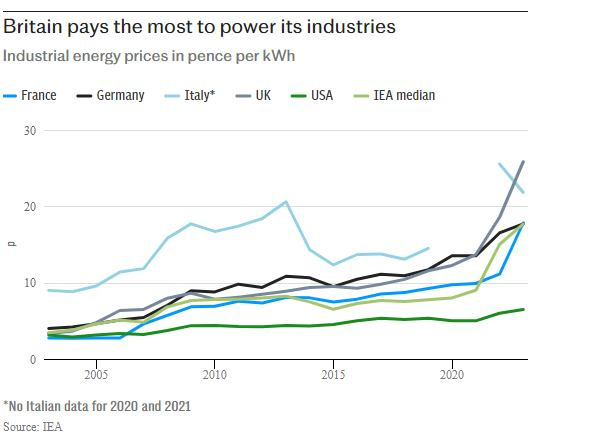

The hindrances to production can be overcome by copying other countries. Low cost energy supply can be prioritised and a minimum of strategic industries protected. The Irish model for financial services might also be explored (see Note 2).

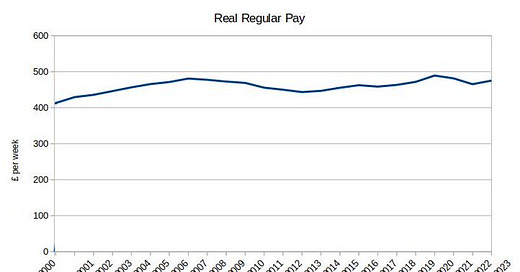

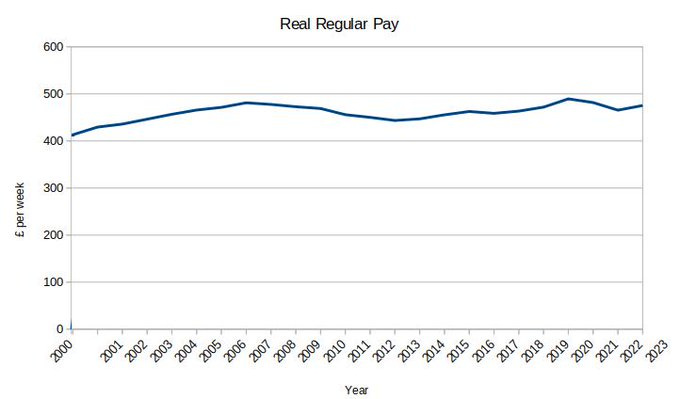

We might think ‘if it was so easy why isn’t it done?’. The answer to this question is that the Conservatives, Labour and the Treasury have targeted wage inflation above other economic variables. They have been very successful, real wages have scarcely increased since 2004:

While people in many other countries have got richer the British government has deliberately kept us poor by targeting wages. Migrant workers have been used to achieve this control. This has pleased the Multinational Companies that lobby government. The Labour Party also desires high migration for ideological reasons (See Why did the English Self Destruct?). Our poverty is a direct result of Internationalism: multinational companies and banks have been pleased at our expense.

The Detail

Productivity growth in the UK had been lagging behind other major economies from 1960 but after the financial crisis in 2008 it dramatically fell into stasis:

It was computer programming, energy, finance, mining, pharmaceuticals and telecoms — which together account for only one-fifth of the economy — that generated three-fifths of the decline in productivity growth after 2008 (See FT).

A Bank of England paper on the productivity crisis points out that cheap labour may have been implicated in the fall in productivity (See Note 1).

The effect of cheap labour is explained as follows. Only small investments were being made in productivity before the productivity crisis but these were sufficient to increase productivity by c.2% a year. Even though the required investments are small an employer faced with investing £300 a year per employee to obtain greater productivity would be very tempted to avoid this if they could obtain employees for £300 a year less in wages. The government used an open door migration policy to allow this route to maintaining profits without investment.

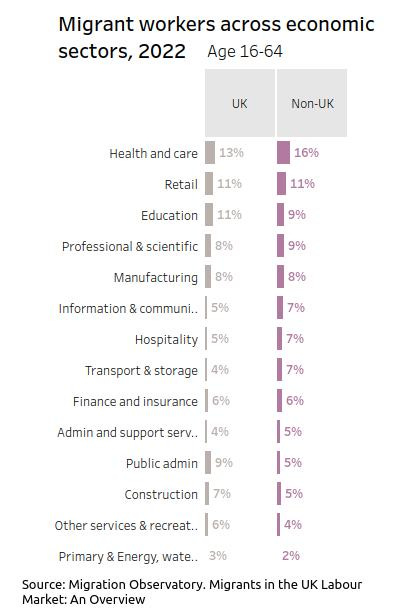

The British government made a point of focusing on importing skilled workers to compete with domestic workers. They boasted of this whilst muttering about training British staff etc. The cheap labour in Britain did not just involve care workers etc. In fact Health and Care only accounts for a sixth of migrant workers. Much of the immigrant work force involved qualified labour that was imported because it could reduce skilled wage rates.

(Source: Migration Observatory Note that about 13% of migrants are needed to deal with the health and care of imported workers and their families. Only 3% of migrant workers were extra staff for the health and care industries).

A big problem with falling behind in productivity investment is that the skills and money required to catch up gets greater as time goes on. A company that is 10 years behind in its production technology and methods finds it harder to update than a company that is 1 year behind. Antiquated companies become forced to rely ever more on labour rather than improving productivity.

Mass migration also causes inflation.

Another, major problem with the UK economy is that activity is becoming ever more focused in less productive industries, the economy is becoming imbalanced:

(Source: House of Commons Library)

In the service sector the highly profitable Financial and Insurance activity is being replaced by the Hospitality industry which is only a fifth as productive per worker.

(Source of data: Commons Library. Productivity is expressed as % of Gross Value Added per worker. Real Estate should be ignored in the table above because it uses ‘imputed rents’ which do not contribute to the economy).

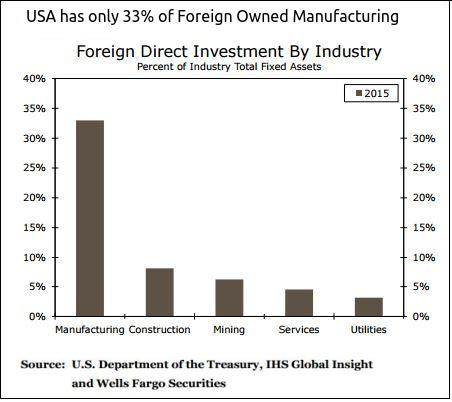

The sale of British companies to foreign competitors has had pernicious effects. About 61% of British manufacturing companies with over 500 employees are now foreign owned (source: Commons question). Most of these companies were purchased because they were profitable or had a large customer base.

In comparison, the USA has only about 33% foreign ownership of manufacturing:

The sale of UK industry to foreign companies means that many of our manufacturing companies have become assembly plants. The factories look highly ‘productive’ because they employ almost no-one to produce thousands of vehicles and other goods. They just bolt together parts made elsewhere. The UK has not just lost its ownership of manufacturing but has also lost the engineering and skill base to recover.

Having sold two thirds of our high productivity, high profit manufacturing industries to foreign companies, various pundits point out that foreign owned companies in the UK have higher productivity than the remaining domestic companies so we should sell all of our industry. We could indeed replace all of our manufacturing with assembly operations but then we would have no manufacturing jobs left and little bonus for the economy.

Productivity is not about how hard you work, it is about the money you make per hour of work, or, at the industry level, how much is made per worker. It is clear from the table above that the public sector (admin &support), health and care, Retail and Hospitality are particularly negative for national productivity.

The government has also ignored the need for strategic industries such as energy, electronics and metals production. These industries are heavily subsidised in other countries but the UK government has insisted on our domestic producers competing with little assistance from subsidies or tariffs.

The abandonment of strategic industries means that the UK is no longer a military power. Our war materials would be exhausted within a week or two of any major conflict. A conflict with China would be especially disastrous.

Our energy prices are a disgrace:

The UK should install nuclear power, preferably using Rolls Royce modular reactors (not foreign reactors). Wind and solar do not work well in the winter. Nuclear is the most reliable back up.

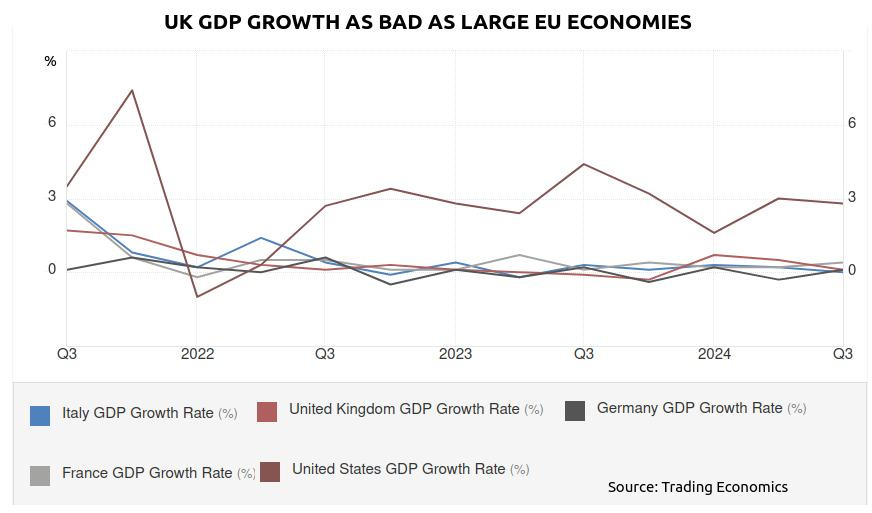

The only good news is that the EU has an approach to their economy that is similar to that of the UK:

The USA has a booming economy relative to the EU.

Note 1: How cheap labour affects productivity.

The fall in productivity growth: causes and implications Silvana Tenreyro, External MPC Member, Bank of England

“Pessoa and van Reenen stressed the role of the UK’s flexible labour market in facilitating a fall in real wages, as well as an increase in the cost of capital following the [financial] crisis. But this is probably not the whole story. Higher levels of uncertainty post-crisis may also have led firms to opt for labour over capital – employment decisions that can now be more easily reversed – rather than invest in new capital. Higher uncertainty and lower income expectations may also have increased households’ desired labour supply for precautionary motives, contributing to lower real wages. Arguably, uncertainty hit harder in the UK as finance represented a much bigger share of the economy.”

Note 2: The Irish Model

Ireland has a GDP per capita (PPP) of $115625 in 2023, more than double the UK value ($54126). This was due to the creation of the The Irish Financial Services Centre (IFSC) which launders money in the EU the the low corporation tax rates are also attractive to overseas companies. Ireland looks like it could be a model for the UK but unfortunately the Irish model is only hugely beneficial for a small country because it relies on financial services. However, it would benefit the UK financial services sector.

Wonderful piece. But emotion aside, a naive question from a non-economist who's studied the 1840s a bit: how do you see tariffs working without (it seems) inevitably driving production abroad and pushing up prices? Trump can do tariffs (lucky orange man) because the huge US is its own economy. But us?